“Change” for the Better

The national War on Poverty is poised to make a big “change” —

and Arkansas’ own soldiers in the fight stand at the ready!

Change is good.

And change is at the heart of a bold new concept being embraced by the nationwide poverty-fighting network known as “Community Action.” Change that seeks not only to elevate those most in need to a new level of self-sufficiency, but also to usher in a new era of accountability and transparency.

Which is to say, a powerful national agent in the struggle against poverty is adopting an exciting new approach designed to please both the idealists who want to see government do more to help its most vulnerable populations—and the realists who want to know that their tax dollars are being well spent.

Nor will the effects of these developments be seen solely on the national scale: Arkansas’s own Community Action Agencies will soon be following suit with their own incarnation of this innovative concept.

Change, the Subject

People sometimes refer to the nation’s over-1000 Community Action Agencies as the “best-kept secret” in America’s War on Poverty—but they have been at the forefront of our country’s efforts to offer the neediest of its citizens a means to rise above their challenges. And now Community Action, for all of its past successes, is about to see a major “change.”

At its heart, the concept known as the “National Theory of Change” is about—despite all the warnings you may have heard that you’d be happier off not knowing!—how the sausage is made. It’s about connecting the dots and showing how you get from A to B: demonstrating how you move from good, heartfelt intentions to solid, substantive results.

Community Action Agencies—CAAs for short—came into existence during the days of LBJ, based on a concept that was as true then as it is today: Nobody knows what a community needs better than the people who live there. President Lyndon Johnson intended each CAA to be like a commando unit in his “War on Poverty,” each with its own specific mission on its own particular front, while all united towards a shared, overall goal. In this way, each agency is uniquely designed to address the concerns in its own proverbial backyard, while still working in tandem with fellow agencies at both the state and national levels to fight a common enemy: poverty.

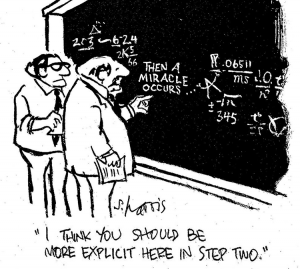

There’s a famous cartoon of two old professor types pondering an elaborate equation written on a chalkboard. One professor is pointing to the middle of the formula where—smack dab in the center of all the numbers and symbols—are written the words, Then a miracle occurs. To his colleague, he advises, “I think you should be more explicit here in step two.”

There’s a famous cartoon of two old professor types pondering an elaborate equation written on a chalkboard. One professor is pointing to the middle of the formula where—smack dab in the center of all the numbers and symbols—are written the words, Then a miracle occurs. To his colleague, he advises, “I think you should be more explicit here in step two.”

This is where the Theory of Change comes in. On the left side of the equation are the assistance programs offered by any given Community Action Agency. These can vary from agency to agency depending on local needs, but they might include the likes of Head Start, help with utility bills, housing assistance, or a food bank—or some combination of the above.

On the right side of the equation, after the “equals” sign, are the desired goals: Reduce poverty. Increase self-sufficiency. Encourage community involvement. All of which—most would agree—are worthwhile goals. But the question remains: What about that middle step? How are we getting from A to B? Are these programs actually getting us closer to these goals? What’s in this sausage?

In “Theory”

These are exactly the sorts of hard questions that led the national network of CAAs to sit down for a serious bout of self-examination—a process that would see it refining not only its core beliefs, but its overall goals—and its commitment to accountability. The network found itself asking not just “Are these programs successfully working towards the elimination of poverty?” but “How are these programs working towards the elimination of poverty?”

The result of this programmatic soul-searching was the introduction of the National Theory of Change. No longer would “Then a miracle occurs” be an adequate assumption to make about the effectiveness of the network’s efforts. This would be a new recommitment to accountability—one to hearten both those seeking reassurance that the country is winning the battle against poverty, and those wanting confirmation that the funds being spent in the battle are not being spent frivolously or fruitlessly.

The result of this programmatic soul-searching was the introduction of the National Theory of Change. No longer would “Then a miracle occurs” be an adequate assumption to make about the effectiveness of the network’s efforts. This would be a new recommitment to accountability—one to hearten both those seeking reassurance that the country is winning the battle against poverty, and those wanting confirmation that the funds being spent in the battle are not being spent frivolously or fruitlessly.

In other words, something to make everybody happy: results.

A Change is Gonna Come

No wonder, then, that one of the chief tools in putting the National Theory of Change into practice is a Community Action performance management system known as ROMA (an acronym for “Results-Oriented Management & Accountability”).ROMA is one of the key components in a dynamically interactive measurement system that determines local needs, creates a strategic plan to address those needs, and then evaluates the success of the plan. Community Action is like a machine with many parts—each of which is carefully monitored to keep precisely calibrated while the overall mechanism is held steady through an exacting hierarchy of standards designed to ensure effectiveness and efficiency at the agency, state, and federal levels.

The National Theory of Change, then, serves as a final puzzle piece to complete a big-picture approach to fighting poverty that is as equally within a local community as it as on a national scale. This is a method that takes no assumptions for granted, asking challenging questions about how best to solve a challenging problem: the intractable dilemma of persistent poverty in a nation of plenty. It is a new path to answering an old question, with a renewed belief—whether it’s via a single individual reinventing him- or herself out of poverty and into self-sufficiency, or through a nationwide collective of partnered organizations finding a fresh perspective on a reinvigorated goal—in the power of change.

The National Theory of Change, then, serves as a final puzzle piece to complete a big-picture approach to fighting poverty that is as equally within a local community as it as on a national scale. This is a method that takes no assumptions for granted, asking challenging questions about how best to solve a challenging problem: the intractable dilemma of persistent poverty in a nation of plenty. It is a new path to answering an old question, with a renewed belief—whether it’s via a single individual reinventing him- or herself out of poverty and into self-sufficiency, or through a nationwide collective of partnered organizations finding a fresh perspective on a reinvigorated goal—in the power of change.

A downloadable PDF of this article is available here.